Summary

Over the past year I’ve investigated potential interventions against respiratory illnesses. Previous results include “Enovid nasal spray is promising but understudied”, “Povidone iodine is promising but understudied” and “Humming will solve all your problems no wait it’s useless”. Two of the iodine papers showed salt water doing as well or almost as well as iodine. I assume salt water has lower side effects, so that seemed like a promising thing to check. I still believe that, but that’s about all I believe, because papers studying gargling salt water (without nasal irrigation) are few and far between.

I ended up finding only one new paper I thought valuable that wasn’t already included in my original review of iodine, and it focused on tap water, not salt water. It found a 30% drop in illness when gargling increased in frequency from 1 time per day to 3.6 times, which is fantastic. But having so few relevant papers with such small sample sizes has a little alarm going off in my head screaming publication BIAS publication BIAS. So this is going in the books as another intervention that is promising but understudied, with no larger conclusions drawn.

Papers

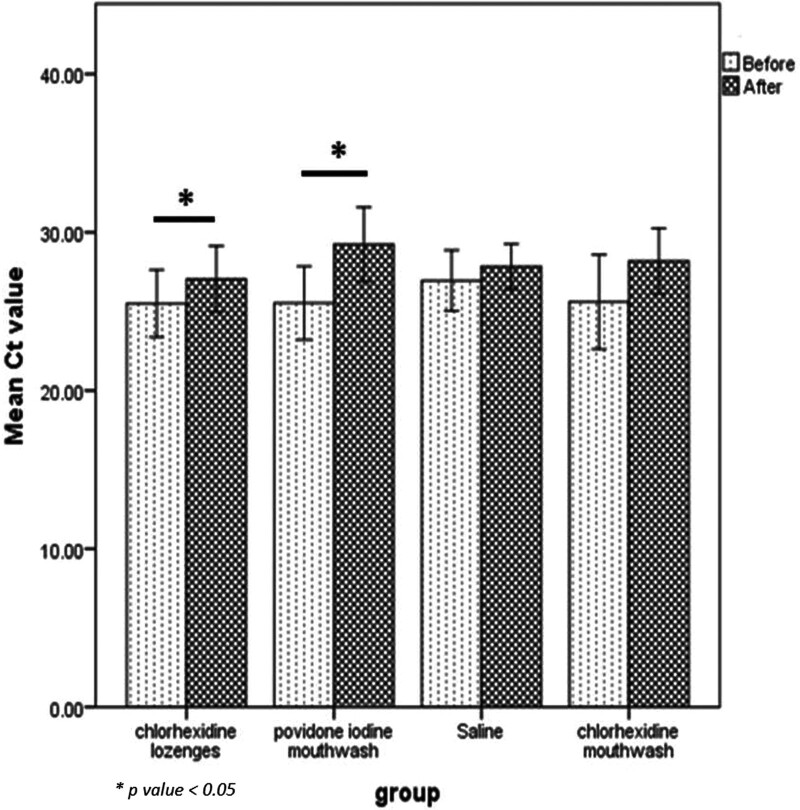

Estimating salivary carriage of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in nonsymptomatic people and efficacy of mouthrinse in reducing viral load: A randomized controlled trial

Note that despite the title, they only gave mouthwashes to participants with symptoms.

This study had 40 participants collect saliva, rinse their mouth with one of four mouthwashes, and then collect more saliva 15 and 45 minutes later . Researchers then compared compared the viral load in the initial collection with the viral load 15 and 45 minutes later. The overall effect was very strong: 3 of the washes had a 90% total reduction in viral load, and the loser of the bunch (chlorhexidine) still had a 70% reduction (error bars fairly large). So taken at face value, salt water was at least as good as the antiseptic washes.

(Normal saline is 0.9% salt by weight, or roughly 0.1 teaspoons salt per 4 tablespoons water)

[ETA 11/19: an earlier version of this post incorrectly stated 1 teaspon per 4 tablespoons. Thank you anonymous]

This graph is a little confusing: both the blue and green bars represent a reduction in viral load relative to the initial collection. Taken at face value, this means chlorhexidine lost ground between minutes 15 and 45, peroxide and saline did all their work in 15 minutes, and iodine took longer to reach its full effect. However, all had a fairly large effect.

My guess is this is an overestimate of the true impact, because I expect an oral rinse to have a greater effect on virons in saliva than in cells (where the cell membrane protects them from many dangers). Saline may also inflate its impact by breaking down dead RNA that was detectable via PCR but never dangerous.

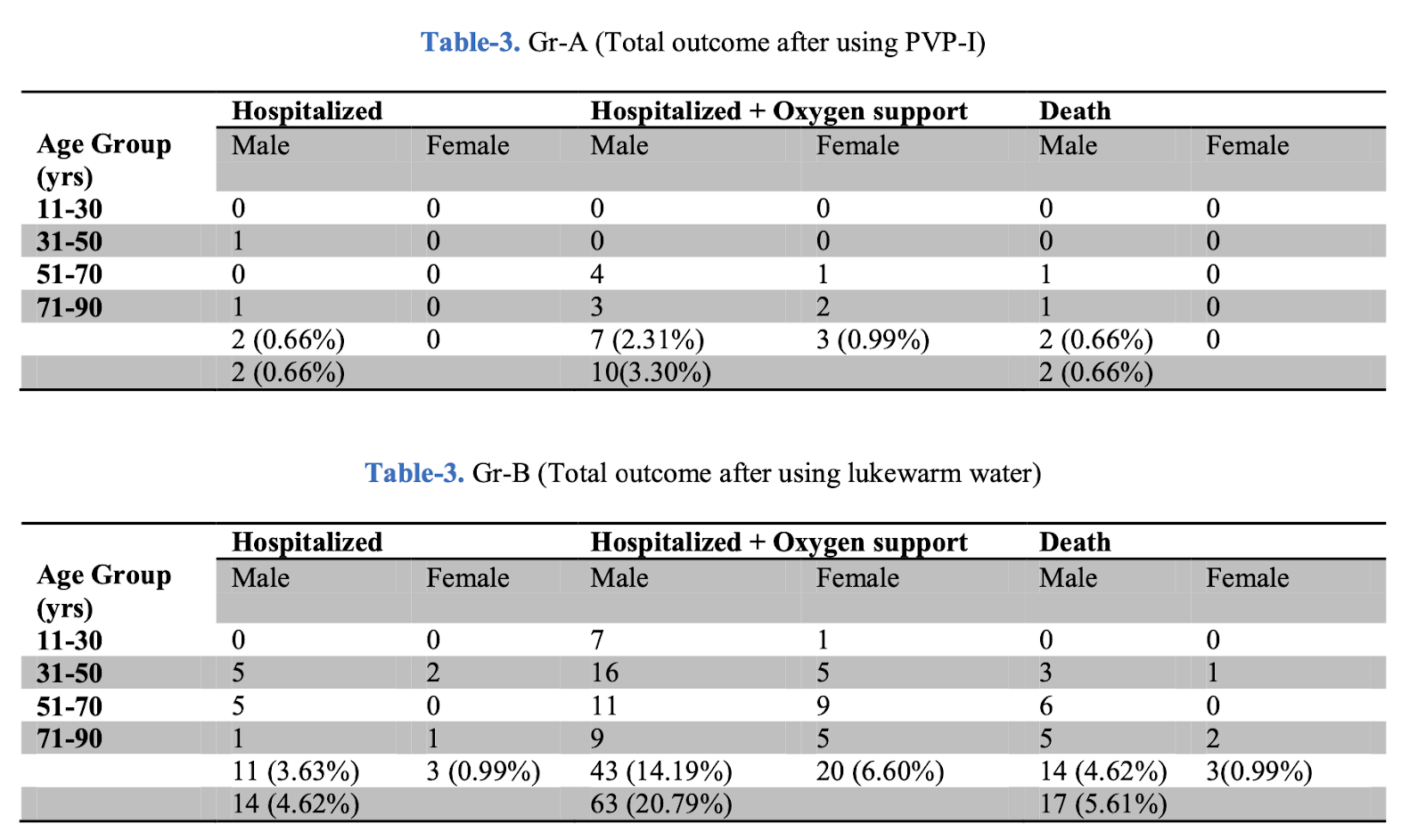

The short-term effect of different chlorhexidine forms versus povidone iodine mouth rinse in minimizing the oral SARS-CoV-2 viral load: An open label randomized controlled clinical trial study

This study had a fairly similar experimental set up to the previous: 12 people per group tried one of three mouth washes, or a lozenge. Participants collected saliva samples immediately before and after the treatments, and researchers compared (a proxy for) viral loads between them.

Well, kind of. The previous study calculated the actual viral load and compared before and after. This study calculated the number of PCR cycles they needed to run before reaching detectable levels of covid in the sample. This value is known as cycle threshold, or Ct. It is negatively correlated with viral load (a smaller load means you need more cycles before it becomes detectable), but the relationship is not straightforward. It depends on the specific virus, the machine set up, and the existing cycle count. So you can count on a higher Ct count representing an improvement, but a change of 4 is not necessarily twice as good as a change of 2, and a change from 30->35 is not necessarily the same as a change from 20->25. The graph below doesn’t preclude them doing that, but doesn’t prove they did so either. My statistician (hi Dad) says they confirmed a normal distribution of differences in means before the analysis, which is somewhat comforting.

This study found a significant effect for iodine and chlorhexidine lozenges, but not saline or chlorhexidine mouthwash. This could be accurate, an anomaly from a small sample size, or an artifact of the saline group having a higher starting Ct value (=lower viral load) to start from.

Prevention of upper respiratory tract infections by gargling: a randomized trial

This study started with 387 healthy volunteers and instructed them to gargle tap (not salt) water or iodine at least three times a day (the control and iodine group also gargled water once per day). For 60 days volunteers recorded a daily symptom diary. This set up is almost everything I could ask for: it looked at real illness over time rather than a short term proxy like viral load, and adherence was excellent. Unfortunately, the design were some flaws.

Most notably, the study functionally only counted someone as sick if they had both nose and throat symptoms (technically other symptoms counted, but in practice these were rare). For a while I was convinced this was disqualifying, because water gargling could treat the pain of a sore throat without reducing viral load. However the iodine group was gargling as often as the frequent watergarglers, without their success. Iodine does irritate the throat, but gargling iodine 3 times per day produced about as much illness as water once per day. It seems very unlikely that iodine’s antiviral and throat-irritant properties would exactly cancel out.

Taking the results at face value, iodine 3x/day + water 1x/day was no better than water 1x/day on its own. Water 3.6x/day led to a 30% reduction in illness (implicitly defined as lacking throat symptoms)

The paper speculates that iodine failed because it harmed the microbiome of the throat, causing short term benefits but long term costs. I liked this explanation because I hypothesized that problem in my previous post. Alas, it doesn’t match the data. If iodine traded a short term benefit for long term cost, you’d expect illness to be suppressed at first and catch up later. This is the opposite of what you see in the graph for iodine. However it’s not a bad description of what we see for frequent water gargling – at 15 days, 10% more of the low-frequency water garglers have gotten sick. At 50 days it’s 20% more – fully double the proportion of sick people in the frequent water gargler group. For between 50 and 60 days, the control group stays almost flat, and the frequent water garglers have gone up 10 percentage points.

What does this mean? Could be noise, could be gargling altering the microbiome or irritating the throat, could be that the control group ran out of people to get sick. Or perhaps some secret fourth thing.

None of the differences in symptoms-once-ill were significant to p<0.05, possibly as a result of their poor definition of illness, or the fact that the symptom assessment was made a full 7 days after symptom onset.

Assuming arguendo that gargling water works, why? There’s an unlikely but interesting idea in another paper from the same authors, based on the same data. They point to a third paper that demonstrated dust mite proteins worsen colds and flus, and suggest that gargling helps by removing those dust mite proteins. Alas, their explanation of why this would help for colds but not flus makes absolutely no goddamn sense, which makes it hard to trust an already shaky idea.

A boring but more reasonable explanation is that Japanese tapwater contains chlorine, and this acts as a disinfectant.

Dishonorable Mention: Vitamin D3 and gargling for the prevention of upper respiratory tract infections: a randomized controlled trial

I silently discarded several papers I read for this project but this one was so bad I needed to name and shame.

The study used a 2×2 analysis examining vitamin D and gargling with tap water. However it was “definitively” underpowered to detect interactions, so they combined the gargling with and without vitamin D vs. no gargling with and without D into groups, without looking for any interaction between vitamin D and gargling. This design is bad and they should feel bad.

Conclusion

Water (salted or no) seems at least as promising an antiviral as other liquids you could gargle, with a lower risk of side effects. So if you’re going to gargle, it seems like water is the best choice. However I still have concerns about the effect of longterm gargling on the microbiome, so I am restricting myself to high risk situations or known illness. However the data is sparse, and ignoring all of this is a pretty solid move.

Thank you to Lightspeed Grants and my Patreon patrons for their support of this work. Thanks to Craig Van Nostrand for statistical consults.

There is a $500 bounty for reporting errors that cause me to change my beliefs, and an at-my-discretion bounty for smaller errors.