Ketamine is an anesthetic with growing popularity as an antidepressant. As an antidepressant, it’s quite impressive. When it works, it’s often within hours- a huge improvement over giving a suicidal person a pill that might work 6 weeks from now. And it has a decent success rate in people who have been failed by several other antidepressants and are thus most in need of a new option.

The initial antidepressant protocols for ketamine called for a handful of uses over a few weeks. Scott Alexander judged this safe, and I’m going to take that as a given for this post. However, new protocols are popping up for indefinite, daily use. Lots of medications are safe or worth it for eight uses, but harmful and dangerous when used chronically. Are these new continuous use protocols safe?

That’s a complicated question that will require several blog posts to cover. For this post, I focused on what academic studies of test tube neurons could tell us about cognitive damage, because I know which organ my readers care about the most.

Reasons to doubt my results

First off, my credentials are a BA in a different part of biology and a willingness to publish. In any sane world, I would not be a competitive source of analysis.

My conclusions are based on 6 papers studying neurons in test tubes, 1.5 of which disagreed with the others. In vitro studies have a number of limitations. At best, they test the effect on one type of cell, in a bed of the same type of cell. If any part of the effect of ketamine routes through other cells (e.g. it might hypothetically activate immune cells that damage the focal cell type), in vitro studies will miss that. It will also miss positive interactions- e.g., it looks like ketamine does stress cells out somewhat, in ways your body has protocols to handle. If this effect is dominant, in vitro would make ketamine look more harmful than it is in practice.

And of course, there’s no way to directly translate in vitro effects directly into real world effects. If ketamine costs you 0.5% of your brain cells, what would that do to you? What would 5% do? In vitro studies don’t tell us that.

All studies involved a single exposure of cells to ketamine (lasting up to 72 hours). If there are problems that come from repeated use rather than total consumption, in vitro can’t show it. However, I consider it far more likely that repeated exposures are much safer than receiving the same dose all at once.

Lastly, in vitro spares the ketamine from any processing done by the liver, which means you are testing only* ketamine and not its byproducts (with the exception of one paper, which also looked at hydronorketamine and found positive results).

[*Processing in neurons might not be literally zero, but is small enough to treat it as such for our purposes]

Tl;dr

I will describe each of the papers in detail, but let me give you the highlights.

Of 6 papers (start of paper names in parentheses):

- 2 found neutral to positive effects at doses higher than you will ever take

- Highest dose with no ill effect:

- 2000uM for 24 hours (Ketamine incudes…)

- 500uM for 24 hours (but 100uM had positive effects) (Ketamine causes…)

- Highest dose with no ill effect:

- 2 found neutral to positive effects at dose you might achieve, but either didn’t test higher doses or found negative effects

- 1 uM for 72 hours (Ketamine increases…) but 0.5uM for 24 hours was better

- 1 uM for 24 h (nothing higher tested) ((2r,6r)…)

- 1 found no cellular mortality from ketamine on its own, but that it mitigated the effect of certain inflammatory molecules that would otherwise kill cells (ketamine prevents…)

- 1 found that ketamine killed cells at a dose you might take.

- Lowest dose tested: 0.39uM for 24 hours (The effects of ketamine…). This is far less than where other papers found positive effects, and I’m not sure why.

- This paper goes out of its way to associate ketamine with date rape in the first paragraph, which is both irrelevant and unfounded, so maybe the authors’ have a negative bias.

- On the other hand, it calls cell mortality of up to 30% “relatively low toxic outcomes”, which sounds excessively positive.

For calibration: I previously estimated that a 100mg troche leads to a median peak concentration of less than 0.46uM, and a total dose of less than 2.8uM*h (to calculate total dose for each of the above papers, just multiply the concentration given by the time given. 1 uM for 24 hours = 24uM*h).

By positive effects, I mean one of two things: ketamine-exposed cells grew bigger and grew more connections with other cells; or, ketamine-exposed test tubes had more cells than their controls, which could mean cells multiplied, or that ketamine slowed cell death (one paper examined these separately, and the answer seemed to be “both.”). This appears to happen because ketamine stimulates multiple cell-growth triggers, such as upregulating BDNF and the mTOR pathway.

The primary negative effect is cell death, which stems from an increase in reactive oxidative species (you know how you’re supposed to eat blueberries because they contain antioxidants? ROS is the problem antioxidants solve). Unclear if there are other pathways to damage.

It doesn’t surprise me at all that two contradictory effects are in play at the same time. In fact, it wouldn’t surprise me if the positive effects were triggered by the negative- it’s not unusual in biology for small amounts of stress to trigger coping mechanisms that do more good than the stress did harm. For example, exercise also produces reactive oxidative species. Approximately everything real that helps with “detoxification” does so by annoying the liver into producing helpful enzymes.

The most actionable thing this post could do is give you the “safe” dose of ketamine”. Unfortunately, it’s hard to translate the research to a practical dose. There are several factors that might matter for the damage done by a drug:

- The peak concentration (generally measured in µM = µmol/L, or ng/ml, which is uM*238)

- The total exposure of cells to the drug, measured in concentration*time

- How much your body is able to repair the damage from a drug. This will generally be higher when the total exposure is divvied up into many small exposures instead of one large one.

- Alas, every study in existence uses a single large dose. But it probably doesn’t matter, because neurons in isolation are missing some antioxidative tools and the ability to replenish what they do have. So I’m left to guess how much safer divided doses are, relative to the single large dose used in every paper.

In an ideal world, the test tube neurons would be given ketamine in a way that mimics both the peak concentration and the total exposure. No one is even trying to make this happen. For most ways you’d receive ketamine for depression, you get an immediate burst followed by a slow decline. But for in vitro work, they dump a whole bunch of ketamine in the tube and let it sit there. Without the liver to break the ketamine down, the area under the curve is basically a rectangle. This makes it absolutely impossible for a test tube to replicate both the peak concentration and the total dose a human would be exposed to. The curves just look different.

[Statistical analysis by MS Paint]

In practice, and excluding the one negative paper, an antidepressant dose is rarely if ever going to reach the peak dose given to the test tube. You’re also not going to have anywhere near that long an exposure. My SUPER ASS PULLED, COMPLETELY UNCREDENTIALED, IN-VITRO ONLY, NOT MEDICAL ADVICE guess is that unless you are unlucky or weigh very little, a 100mg troche of ketamine will not do more oxidative damage than your body is able to repair in a few days (this excludes the risk of damage from byproducts).

There’s a separate concern about tolerance and acclimation, which none of these papers looked at, that I can’t speak to.

Papers

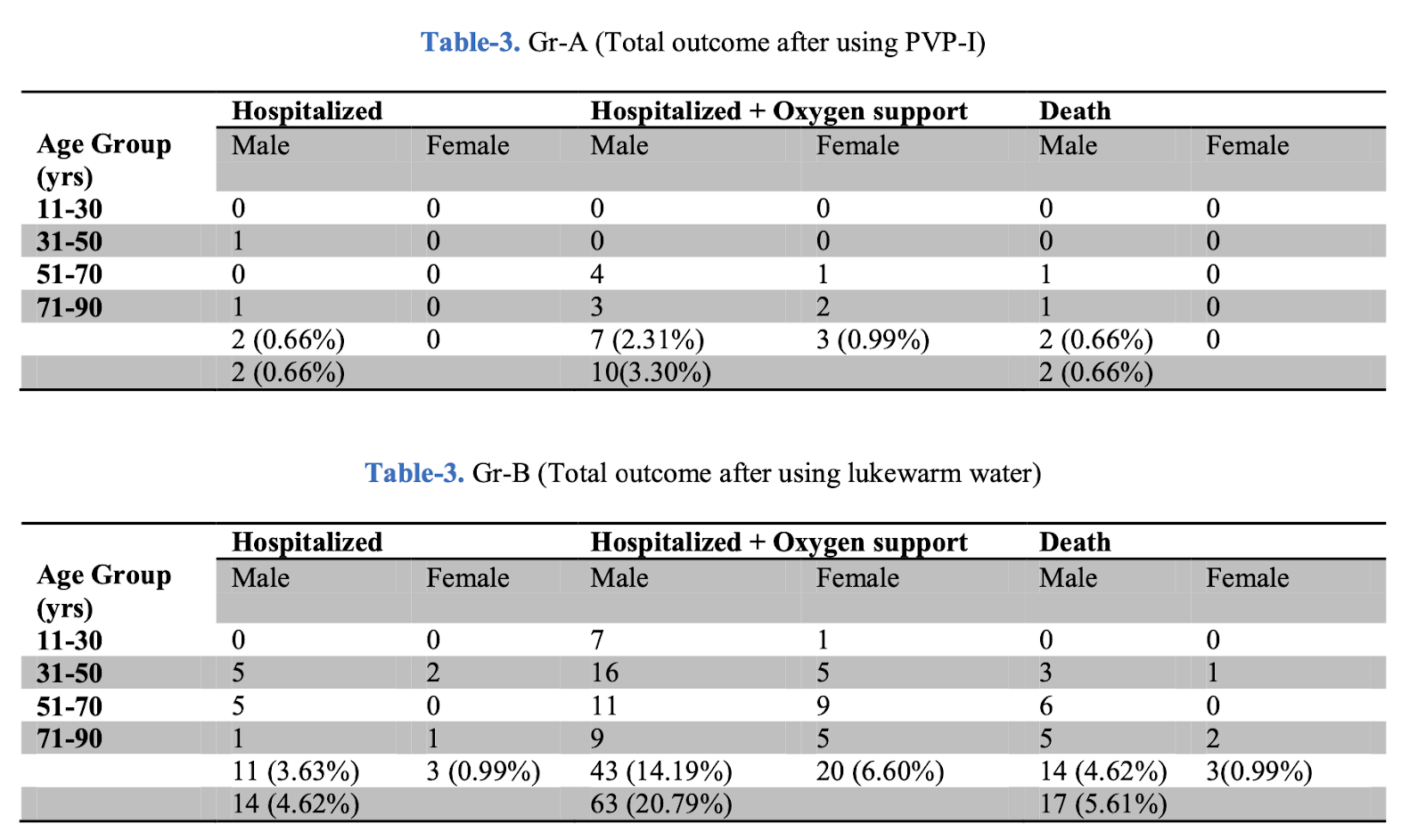

Warning: most of these papers used bad statistics and they should feel bad. Generally, when you have multiple treatment arms in a study that receive the same substance at different doses, you do a dose-response analysis- in essence, looking for a function that takes the dose as an input and outputs an effect. This lets you detect trends and see significance earlier.

What these papers did instead was treat each dose as if it were a separate substance and evaluate their effects relative to the control individually. This faces a higher burden to reach statistical significance.

Because of this, if there’s an obvious trend in results, and the difference from control is significant at higher levels, I report each individual result as if it’s statistically significant. I haven’t redone the math and don’t know for sure what the statistical significance of the effect is.

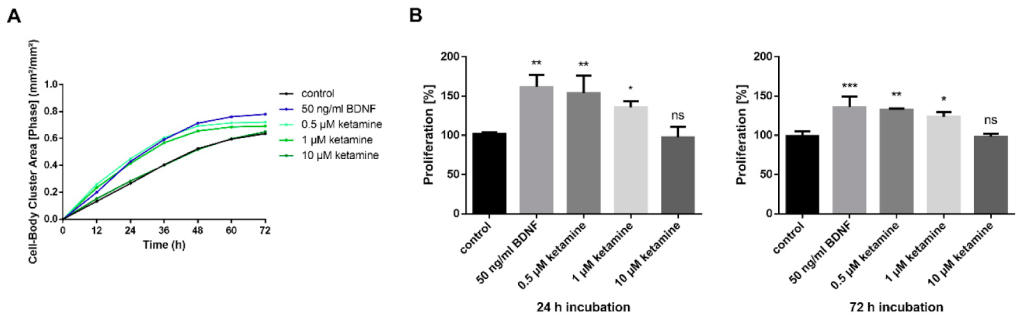

Ketamine Increases Proliferation of Human iPSC-Derived Neuronal Progenitor Cells via Insulin-Like Growth Factor 2 and Independent of the NMDA Receptor

Dose: 0.5uM to 10 uM

Exposure time: 24-72 hours

Interval between end of exposure and collection of final metric: 72 hours

As you can see in the bar chart, ketamine was either neutral or positive. However, less ketamine was more beneficial- there was more growth at the lowest dose of ketamine than the highest (which was indistinguishable from control), and more growth after a 24 hour exposure than a 72 hour exposure.

To achieve the same peak dosages, you’d need ~100 – 2000mg sublingual ketamine. To achieve the same total exposure, you’d need 430 doses of 100mg ketamine at the low end (for 0.5mM for 24 hours) to 24,000 doses at the high end (10uM for 72 hours) (assuming linearity of dose and concentration, which is probably false).

The following isn’t relevant, but it is interesting: researchers also applied ketamine to some standard laboratory cells (the famous HeLa line, which is descended from cervical cancer) and found it did not speed up cell proliferation- meaning ketamine isn’t an indiscriminate growth factor, but targets certain kinds of cells, including (some?) neurons.

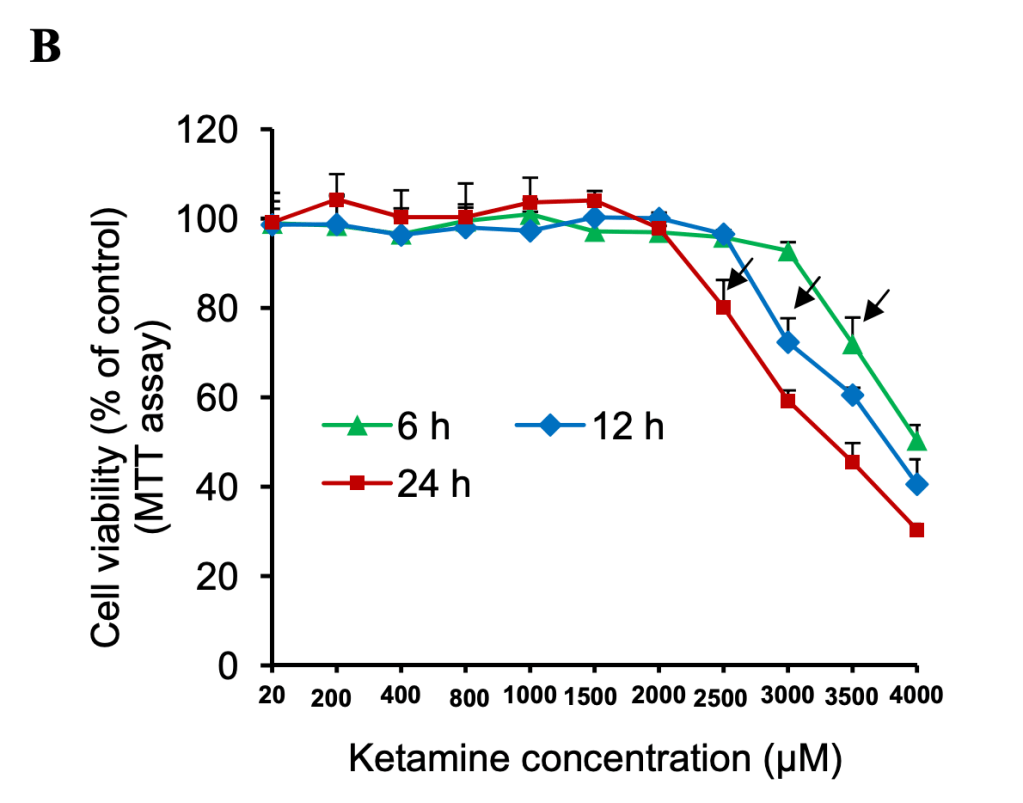

Ketamine Induces Toxicity in Human Neurons Differentiated from Embryonic Stem Cells via Mitochondrial Apoptosis Pathway

Dose: 20uM to 4000 uM

Exposure time: 6-24 hours

Interval between end of exposure and collection of final metric: 72 hours

Don’t let the title scare you- the toxicity was induced at truly superhuman doses (24 hours at 100x what they call the anesthetic dose, which is already 3x what another paper considered to be the anesthetic dose)

Calibration: the lowest dose of ketamine (20 uM) given corresponds to 40x my estimate for median peak concentration after a 100mg troche.

Chart crimes: that X-axis is neither linear nor any other sensible function.

Chart crimes aside, I’m in love with this graph. By testing a multitude of doses at three different lengths of exposure, it demonstrates 6 things:

- Total exposure matters- a constant concentration of 300uM showed negative effects at 12 hours but not 6.

- After a threshold is reached, the negative effect of total dose is linear or mildly sublinear.

- Peak dosage matters separate from total dose. If that weren’t true, doubling the dose would halve the time it took to show toxicity.

- Doubling exposure time is roughly equivalent to increasing dosage by 500uM

- At lower doses, longer exposure is correlated with greater cell survival/proliferation. But at higher doses, longer exposure is correlated with lower viability.

- The lowest total exposure required to see negative effects is 21,000uM*h, which would require ~17,500 100mg troches- or one every day for 48 years. Before accounting for any repair mechanisms.

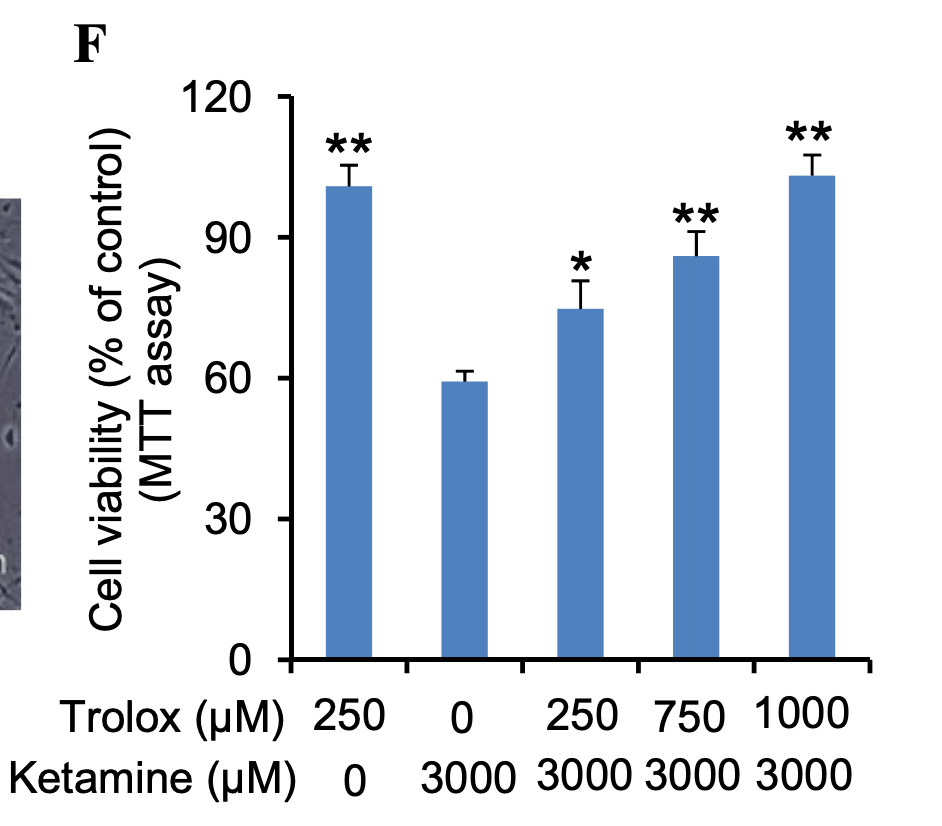

The paper spends a great deal of time asking why ketamine is toxic at high doses, focusing on reactive oxidative species (ROS) (the thing that blueberries fight). This suggests that your body’s antioxidant system likely reduces the damage compared to what we see in test tubes. Unfortunately I don’t know how to translate the dosage of Trolox, their anti-oxidant, to blueberries.

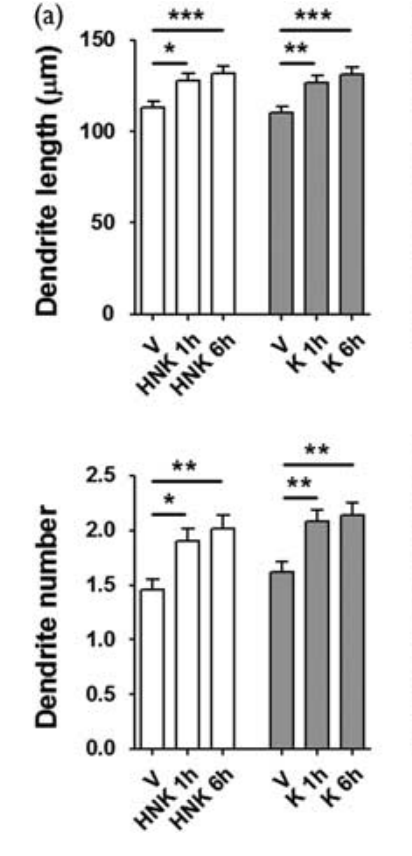

(2R,6R)-Hydroxynorketamine promotes dendrite outgrowth in human inducible pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons through AMPA receptor with timing and exposure compatible with ketamine infusion pharmacokinetics in humans

Dose: 1 uM

Exposure time: 1-6 hours

Interval between end of exposure and collection of final metric: 60 days (!)

Outcome: synaptic growth

Most of the papers I looked at created their neurons from a stem cell line and then briefly ages This paper stands out for aging the cells for a full 60 days before exposing them to 1 uM ketamine (they also tried hydronorketamine, a byproduct of ketamine metabolism. I’ll be ignoring this, but if you see “HNK” on the graph, that’s what it means).

Here we see that ketamine and its derivative significantly increased the number and length of dendrites (the connections between neurons). It’s possible to have too much of this, but in the moderate amounts shown this should lead to an easier time learning and updating patterns.

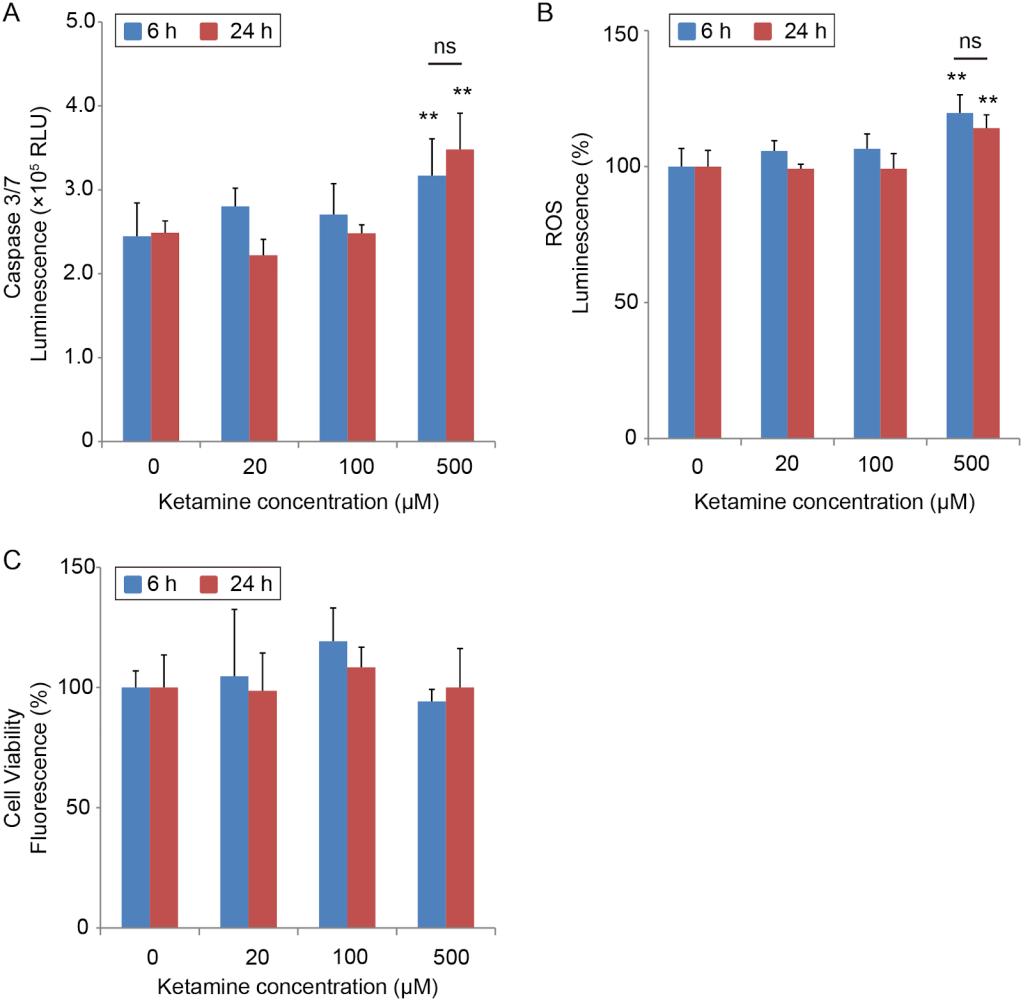

Ketamine Causes Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Neurons

Dose: 20-500 uM

Exposure time: 6-24 hours

Interval between end of exposure and collection of final metric: 0 hours?

This is another paper with a scary title that is not born out by its graphs. It did find evidence of cellular stress (although this is only unequivocal at higher doses), but cell viability was actually higher at lower doses and unchanged at higher doses, and by lower dose I mean “still way more than you’re going to take for depression”

20uM = a higher peak than you will ever experience even under anaesthetic. 20uM for 6 hours has the same cumulative exposure of 42 100mg troches. 100uM for 24 hours has the same cumulative exposure as 142 100mg troches (for the median person)

Capsace 3/7 and ROS luminescence are both measures of oxidative stress (the thing blueberries fight). Cell viability is what it sounds like. There was no statistically significant difference in viability, and eyeballing the graph it looks viability increases with dosage until at least 100uM.

Ketamine Prevents Inflammation-Induced Reduction of Human Hippocampal Neurogenesis via Inhibiting the Production of Neurotoxic Metabolites of the Kynurenine Pathway

Dose: 0.4 uM

Exposure time: 72 hours

Interval between end of exposure and collection of final metric: 7 days

Exposed cells to neurotoxic cytokines, two forms of ketamine, and two other antidepressants, alone and in combination. The dose of ketamine was 400nM or 0.4uM, which is about 1 100mg sublingual troche.

These graphs are not great.

DCX is a signal of new cell growth (good), CC3 is a sign of cell death (bad), Map2 is a marker for mature neurons (good). In general, whatever the change is between the control and IL-* (the second entry on the X axis) is bad, and you want treatments to go the other way. And what we see is the ketamine treatments are about equivalent to the control. .

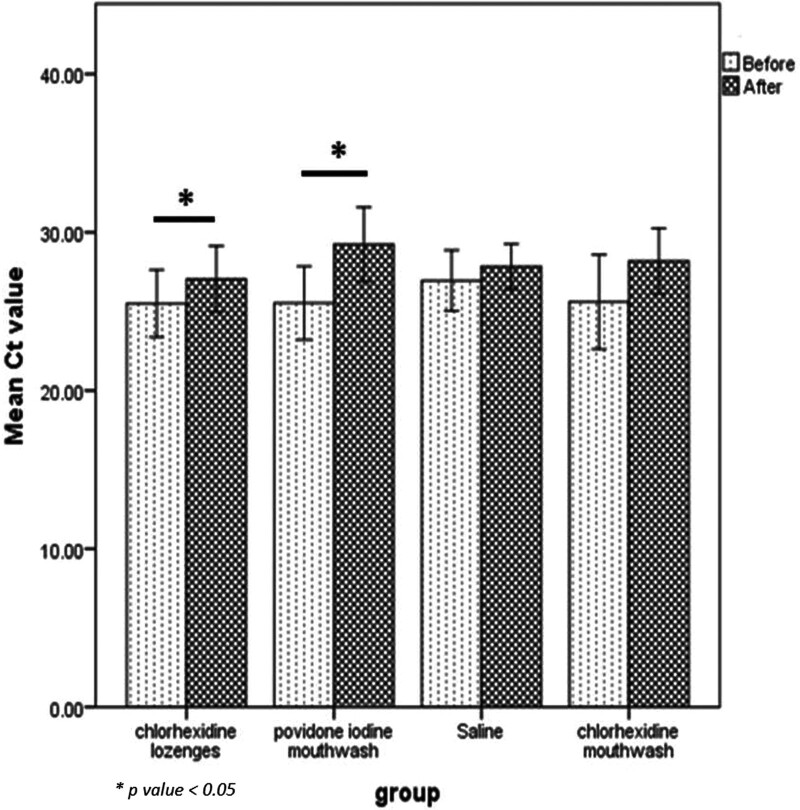

The effects of ketamine on viability, primary DNA damage, and oxidative stress parameters in HepG2 and SH-SY5Y cells (the negative one)

Dose: 0.39-100 uM

Exposure time: 24 hours

Interval between end of exposure and collection of final metric: 0 hours?

(Pink cells are neurons derived from a neurological cancer cell line, Blue cells are liver cells derived from a liver cancer cell line. The red boxes correspond to their estimate of the painkilling, anesthetic, and drug abuse levels of concentration. All conditions were exposed for 24 hours. & means P<0.05; #, P<0.01; $, P<0.001; *, P<0.0001)

This paper found a 20% drop in neuron viability for anesthetic doses of ketamine, and 5% for a painkilling dose (and a milder loss to liver cells). This is compared to an untreated control that lost <1% of cells. They describe this result as “low cytotoxicity” for ketamine. I am confused by this and wonder if they had some pressure to come up with a positive result. On the other hand, the paper’s opening paragraph contains an out-of-left-field accusation that ketamine is a common ingredient in date rape pills, which is irrelevant, makes no sense, and is given no passable justification*, which makes me think at least one author thinks poorly of the chemical. So perhaps I’m merely showing my lack of subject matter expertise, and 20% losses in vitro don’t indicate anything worrisome.

[*They do give a citation, but neither that paper nor the ones it cites offer any reason to believe ketamine is frequently used in sexual assault, just passing mentions. In the anti column we have the facts that ketamine tastes terrible and is poorly absorbed orally, requiring large doses to incapacitate someone. It’s a bad choice to give surreptitiously. Although I wouldn’t doubt that taking ketamine voluntarily makes one more vulnerable.]

Why In Vitro Studies?

Given all their limitations, why did I focus exclusively on in vitro studies? Well, when it comes to studying drug use, you have four choices:

- Humans given a controlled dose in a laboratory.

- All the studies I found were short-term, often only single use, and measured brain damage with cognitive tests. Combine with a small sample size and you have a measurement apparatus that can only catch very large problems. It’s nice to know those don’t happen (quickly), but I also care about small problems that accumulate over time.

- Humans who took large amounts of a substance for a long time on their own initiative.

- This group starts out suffering from selection effects and then compounds the problem by applying their can-do attitude towards a wide variety of recreational pharmaceuticals, making it impossible to untangle what damage came from ketamine vs opiates. In the particular case of ketamine, they also do a lot of ketamine, as much as 1-4 grams per day (crudely equivalent to 11-44 uM*h if they take it nasally, and 2-4x that if injected)

- I initially thought that contamination of street drugs with harmful substances would also be a big deal. However, a friend directed me to DrugsData.org, a service that until 2024 accepted samples of street drugs and published their chemical makeup. Ketamine was occasionally used as an adulterant, but substances sold under the name ketamine rarely contained much beyond actual ketamine and its byproducts.

- Animal studies. I initially dismissed these after I learned that ketamine was not used in isolation in rats and mice (the subjects of almost every animal paper), only in combination with other drugs. However, while writing this up, I learned that this may be due to a difference in use case, rather than a difference in response to ketamine. But when I looked at the available literature there were 6 papers, every one of which gave the rats at least an order of magnitude more ketamine than a person would ever take for depression.

- For the curious, here’s why ketamine usage differs in animals and humans:

- Ketamine is cheap, both as a substance and because it doesn’t require an anesthesiologist. In some jurisdictions, it doesn’t even require a doctor. Animal work is more cost-conscious and less outcome-conscious, so it’s tilted towards the cheaper anesthetic.

- New anesthetics for humans aren’t necessarily tested in animals, so veterinarians have fewer options.

- Doctors are very concerned that patients

hate their experiencenot get addicted to medications, and ketamine can be enjoyable (although not physically addictive). Veterinarians are secure that even if your cat trips balls and spends the next six months jonesing, she will not have the power to do anything about it.

Pictured: a cat whose dealer won’t return her texts.

- ketamine is rare in that it acts as an anesthetic but not a muscle relaxant. For most surgeries, you want relaxed muscles, so you either combine the ketamine with a muscle relaxant or use another drug entirely. However there are some patients where relaxing muscles is dangerous (generally those with impaired breathing or blood pressure), in which case ketamine is your best option.

- Ketamine is unusually well suited for emergency use, because it acts quickly, doesn’t require an anesthesiologist, and can be delivered via shot as well as IV. In those emergencies, you’re not worried about what it can’t do.

- All this adds up to a very different usage profile for ketamine for animals vs. humans.

- For the curious, here’s why ketamine usage differs in animals and humans:

Conclusion

My goal was specifically to examine chronic, low-dose usage of ketamine. Instead, I followed the streetlight effect to one-off prolonged megadoses. I’m delighted at how safe ketamine looks in vitro, but of course, that’s not even in mice.

Thanks

Thanks to the Progress Studies Blog Building Initiative and everyone I’ve talked to for the last three months for feedback on this post. Thanks to my Patreon supporters and the CoFoundation Fellowship for their financial support of my work

This is time consuming work, so if you’d like to support it please check out my Patreon or donate tax-deductibly through Lightcone Infrastructure (mark “for Ketamine research”, minimum donation size $100).