Introduction

Epistemic status: everything is stupid. I’m pretty sure I’m directionally right but this post is in large part correcting previous statements of mine, and there’s no reason to believe this is the last correction. Even if I am right, metabolism is highly individual and who knows how much of this applies to anyone else.

This is going to get really in the weeds, so let me give you some highlights

- 1-2 pounds of watermelon/day kills my desire for processed desserts, but it takes several weeks to kick in.

- It is probably a microbiome thing. I have no idea if this works for other people. If you test it let me know.

- I still eating a fair amount of sugar, including processed sugar in savory food. The effect is only obvious and total with desserts.

- This leads to weight loss, although maybe that also requires potatoes? Or the potatoes are a red herring, it just takes a while to kick in?

- Boswellia is probably necessary for this to work in me, but that’s probably correcting an uncommon underlying defect so this is unlikely to apply widely.

- Stevia-sweetened soda creates desire for sugar in me, even though it doesn’t affect my blood sugar. This overrides the watermelon effect, even when I’m careful to only drink the soda with food.

- My protein shakes + bars also have zero-calorie sweeteners and the watermelon effect survives them. Unclear if it’s about the kind of sweetener, amount, or something else.

- Covid also makes me crave sugar and this definitely has a physiological basis.

- Metabolism is a terrifying eldritch god we can barely hope to appease, much less understand.

Why do I believe these things? *Deep breath* this is going to take a while. I’ve separated sections by conclusion for comprehensibility, but the discovery was messy and interconnected and I couldn’t abstract that out.

Boswellia

Last October I told my story of luck based medicine, in which a single pill, taken almost at random, radically fixed lifelong digestion issues. Now’s as good a time as any to give an update on that.

The two biggest effects last year were doubling my protein consumption, and cratering sugar consumption. I’m still confident Boswelia is necessary for protein digestion, because if I go off it food slowly starts to feel gross and I become unable to digest protein. I’m confident this isn’t a placebo because I didn’t know Boswelia was the cause at the time, so going off it shouldn’t have triggered a change.

As I’ll discuss in a later section, Boswelia is not sufficient to cause a decrease in sugar consumption; that primarily comes from consuming heroic amounts of watermelon. The Boswellia might be necessary to enable that much watermelon consumption, by increasing my ability to digest fiber. I haven’t had to go off Boswellia since I figured out how it helps me, so I haven’t tested its interaction with watermelon.

How does Boswellia affect micronutrient digestion? I have always scored poorly on micronutrient tests. I had a baseline test from June 2022 (shortly after starting Boswellia + watermelon), and saw a huge improvement in October testing (my previous tests are alas too old to be accessible). Unfortunately this did not hold up – my March and June 2023 tests were almost as bad as June 2022. My leading hypotheses are “the tests suck” and “the November tests are the only ones taken after a really long no-processed-dessert period, and sugar is the sin chemical after all”. I hate both of these options.

If we use fuzzier standards like energy level, illness, and injury healing, I’m obviously doing much better. Causality is always hard when tracking effects that accumulate over a year. In that time there’s been at least one other major intervention that contributed to energy levels and mood, and who knows what minor stuff happened without me noticing. But I’d be shocked if improved nutrition wasn’t a major contributor to this.

Illness-wise; I caught covid for the second time in late November 2022, and it was a shorter illness with easier recovery than in April (before any of these interventions started). But that could be explained by higher antibody levels alone. I haven’t gotten sick since then (9 months), which would have been an amazing run for me pre-2022.

My protein consumption (previously 30-40g/day) spiked after I started Boswellia in May 2022 (~100g/day) and then slowly came down. Before November covid I was at ~70g/day. My explanation at the time was that my body had some repairs it had been putting off until the protein was available, and once those were done it didn’t need so much. It spiked again after November covid and only partially came down, I’m still averaging ~100g/day. I’m not sure if I still need that for some reason, or if I’m just craving more calories and satisfying that partially with protein.

Watermelon

In spring 2022 I started eating 1-2 pounds of watermelon per day. This wasn’t a goal-oriented diet or anything, I just really like watermelon and finally realized the only limitations were in my mind. I started eating watermelon when it came into season, before I got covid in April 2022, but didn’t start the serious habit until the later half of my very long covid case. As previously discussed, that May my doctor prescribed me Boswellia in part to aid covid recovery, and a bunch of good things followed (including a disinterest in processed sugar), all of which I attributed to the Boswelia.

The loss of interest in sugar was profound. It wasn’t just that I gained the ability to resist temptation; I mostly didn’t enjoy sugar when I had it. I went from a bad stress eating habit to just… not thinking of sugar as an option when stressed.

My interpretation at the time was “sugar cravings were a pica for real nutrition, as soon as I could digest enough food they naturally went away, fuck you doctors”. It never occured to me the watermelon might be involved because in my mind it was categorized as “indulgence” not “intervention”. Even if it had occured to me to test it, I know now the effect takes at least six weeks to kick in, and I wouldn’t have waited that long. Lucky for science, reality was going to force my hand.

Around October I started wanting sugar again, although not as much as before. I put this down to stress, but that never really made sense: August saw me break my wrist and have a very stressful interpersonal issue without any return in cravings. Then in November I got covid again, and it again created intense sugar cravings, which improved some but never really went away. I thought maybe covid had permanently broken my metabolism. I played with the Boswellia dosing for a while but it didn’t seem to make a difference. Plus my protein digestion stayed the same the whole time, so it seemed unlikely Boswellia had just stopped working.

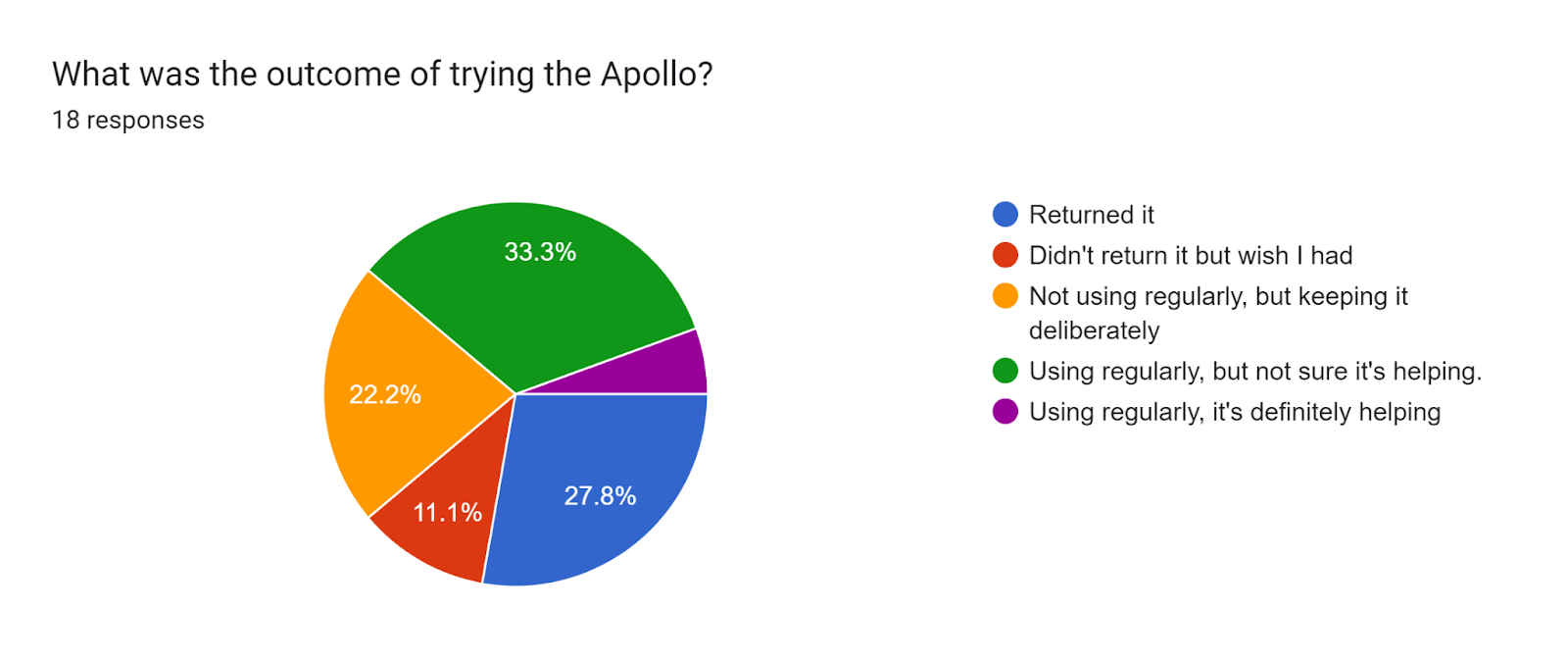

In February 2023 I talked about this with David MacIver of Overthinking Everything, and noticed that the sugar cravings had returned a few weeks after watermelon had gone out of season. I created a graph from my food diary, and it became really obvious watermelon was the culprit.

The effect is even stronger than it looks, because watermelon has sucrose in it. Over summer my sucrose intake is 90% from fruit; over winter it’s dominated by junk.

I figured this out in February 2023. Because I live in a port city in a miracle world, that was late enough in the season to get mediocre watermelon. It took a while to work, but that was true the first time as well (somewhere between 6 weeks and 12, depending on how you count covid time). And you can indeed see where this started on the graph. But five months later it is still replicating the previous year’s success. Sugar cravings were weaker but still present, and certainly came back when I was stressed. The weight loss was slow and stuttering where it had previously been easy. That brings me to my next point.

Stevia-sweetened Soda

In January 2023 my doctor gave me a continuous glucose monitor to play around with. The thought process here was…exploratory. Boswellia is known to lower blood sugar, and helped with (I thought) sugar cravings and many other issues. Covid causes sugar cravings in me, is known to hurt diabetics more, and causes lots of other problems, so maybe that points to blood sugar issues in me? Also I was kind of hoping the immediate feedback would nudge me to eat less sugar.

One of the foods I was most excited to test was 0-calorie soda. I’d always avoided diet soda on the belief that no-calorie sweeteners spiked your insulin and this led to sugar cravings that left you worse off. But when I tried stevia-sweeted Zevia with the GCM my blood glucose levels didn’t move at all, and I didn’t feel any additional drive to eat sugar (compared to my then-high baseline desire – remember this was while I was off watermelon and dessert was amazing).

I was extremely excited about this discovery. I’d given up cola about 18 months before and missed it dearly. Now I had chemical and mathematical proof that no-cal soda was fine. When I had the cola again it made me so happy I was amazed I’d ever managed to give it up before. I began a 2-3 cans/day caffeine-free Zevia cola habit.

This would have been 4-6 weeks before I restarted on watermelon. When the watermelon failed to repeat its miracle I suspected Zevia fairly quickly, but I really, really didn’t want it to be true so I tested some other things first. Finally I had ruled out too many other things, and had a particularly clarifying experience of sudden, strong cravings with nothing else to blame. I gave up Zevia, and immediately lost all desire for sugar. In retrospect the low-sugar-desire days of the previous months were probably not random, but days I happened to not drink Zevia.

Unfortunately this doesn’t obviously show up on the fructose vs sucrose graph and I don’t care enough to export the data and do real statistics. It also doesn’t show up cleanly on my weight graph, because weight is noisy and the effect operates at a substantial delay. But I’ve given it 7 weeks, and I’m definitely losing weight. The current streak is faster than anything I had last year, although it’s too soon to say if that will hold up. . .

Zevia is sweeted with stevia, which seems like it should make stevia an enemy. But my protein shake is also sweetened with stevia (plus something else), and I had at least a bottle/day during the weight loss last year (this is one excuse I gave for testing other potential culprits before Zevia). Maybe the issue is the amount in Zevia, maybe drinking stevia with a lot of protein is better than separately, even when it’s with a meal. Maybe Mercury was in retrograde I give up.

Potatoes and Weight Loss

The no-sugar effect had kicked in in earnest by late May 2022 (I didn’t start a food diary until late June that year, but confirmed the May date by looking at my grocery orders). In July 2022 I went on minimum viable potato diet, in which I ate a handful of baby potatoes every day and demanded nothing else of myself. Within a few days my caloric intake dropped dramatically, and I started to lose weight. This continued late fall, when watermelon went out of season.

The post-potato weight loss was weird, and seemed much too large to be produced by a handful of potatoes. But it was such a strong effect that started so quickly after potatoes that it seemed impossible to be a coincidence.

I mentioned before that the watermelon works on a delay. So maybe I just happened to start eating potatoes the day the watermelon effect kicked in (I don’t have exact timing for this – the first run is complicated by covid and the second by stevia soda and work stress). Maybe I need watermelon and potatoes for some stupid reason. Maybe that 100g of produce was a tipping point, but 100g of anything would have worked. Or maybe that’s just when the summer heat kicked in, since I’ve always eaten less when it was hot out. Maybe it’s not a coincidence the current weight loss kicked in shortly after finishing a stressful, air conditioned gig…

Questions

What is happening with sugar?

The stevia effect appears to be same-day, often kicking in within a few hours and wearing off by the next day, so I assume that’s a metabolic issue. But not one reflected in blood sugar, according to the CGM. Unless the effect kicks in slowly (while also stopping the day I stop drinking it).

The no-sugar effect watermelon takes 4-8 weeks to kick in, and another 4+ to cause weight loss. But between those milestones… I don’t want to brag, but it’s relevant so I think I have to. ~10 weeks after 1-2lbs of watermelon/day my feces become amazing. So amazing they look fake, like they were crafted for an ad for a fiber pill. Enormous without being at all painful because of their perfect consistency. Other bowel movements resent mine for setting unrealistic beauty standards, but they can’t help it, that’s just how they naturally look.

Between the delay and the gold-ribbon poops, I’m pretty sure the watermelon effect works through microbiome changes. Maybe fiber, maybe feeding different bacteria, maybe changing the metabolism of the existing bacteria?

Are you one of those idiots who thinks processed sugar is different than natural sugar?

I regret that I have to answer this with “maybe”. Processed is not well defined here, but it sure seems like a Calorie from watermelon hits me differently than a Calorie from marshmallows; even if they fuel the same amount of metabolism. My guesses for what actually matters are fiber, fructose vs sucrose, water content, and “fuck if I know”. If anyone tries a sugar water + fiber pills diet, please do let me know.

I try to be careful to say I haven’t given up processed sugar, just processed desserts. Lots of savory dishes have a fair amount of sugar (not just carbs) in them. My guess is that if easy, sugar-free prepared food was available I wouldn’t miss the sugar, but in the real world it is too much work to cut it out and I seem to be doing okay as-is

Does it have to be watermelon?

If I’m right about the fructose, fiber, and/or water, no, but I haven’t tested it. Watermelon does have a pretty favorable mix of those (grapes have way more sugar per gram), but its primary virtue is that it is obviously the best fruit and I’d struggle to eat that much of anything else on purpose, much less do so accidentally for months straight. In fact I did try to replace watermelon that winter, but couldn’t find anything I’d eat that much of.

However someone on twitter pointed out that watermelon is unusually high in citrulline (which is used to produce arginine, which is metabolically important). There’s no way I could detect this trend against my overall increase in protein uptake, so I can’t do more than pass this on. If California fails to deliver truly year round watermelon my plan is carrots + citruilline pills, so maybe we’ll find out then.

Why does Boswellia help protein digestion?

I don’t know. Digestion isn’t even included on the list of common effects of Boswellia. All any doctor will tell me is “something something inflammation”, as if I haven’t taken dozens of things with equally strong claims to reducing inflammation.

Last year a reader connected me with a friend who had some very interesting ideas about mast cell issues, and I swear I’m going to look into those any day now…

Conclusion

Everything is stupid, nothing makes sense. If hadn’t lucked into a situation where I was using Boswellia, eating stupid amounts of watermelon, and consuming no Zevia I might never have found out this no-sugar-desire state and would be at least 30 pounds heavier.

PS

If you find yourself thinking “this is great, I’m so sad Elizabeth only publishes a few extremely long posts per year about metabolism that prove nothing”, I have good news! The Experimental Fat Loss substack features multiple posts per month in exactly that genre. It mostly follows the author’s fairly rigorous dietary experiments, but lately he’s been taking case studies from other people as well.