It took me a long time to realize that Bell Labs was cool. You see, my dad worked at Bell Labs, and he has not done a single cool thing in his life except create me and bring a telescope to my third grade class. Nothing he was involved with could ever be cool, especially after the standard set by his grandfather who is allegedly on a patent for the television.

It turns out I was partially right. The Bell Labs everyone talks about is the research division at Murray Hill. They’re the ones that invented transistors and solar cells. My dad was in the applied division at Holmdel, where he did things like design slide rulers so salesmen could estimate costs.

[Fun fact: the old Holmdel site was used for the office scenes in Severance]

But as I’ve gotten older I’ve gained an appreciation for the mundane, grinding work that supports moonshots, and Holmdel is the perfect example of doing so at scale. So I sat down with my dad to learn about what he did for Bell Labs and how the applied division operated.

I expect the most interesting bit of this for other people is Bell Labs’ One Year On Campus program, in which they paid new-grad employees to earn a master’s degree on the topic of Bell’s choosing. I would have loved to do a full post on OYOC, but it’s barely mentioned online and my only sources are 3 participants with the same degree. If you were a manager who administered OYOC or at least used it for a degree in something besides Operations Research, I’d love to talk to you (elizabeth@northseaanalytics.com).

And now, the interview

Elizabeth: How did you get started at Bell Labs?

Craig: In 1970 I was about to graduate from Brown with a ScB in Applied Math. I had planned to go straight to graduate school, and been accepted, but I thought I might as well interview with Bell Labs when they came to campus. That was when I first heard of the One Year On Campus program, where Bell Labs would send you to school on roughly 60% salary and pay for your tuition and books, to get a Masters degree. Essentially, you got a generous fellowship and didn’t have to work as a teaching or research assistant, so it was a great deal. I got to go to Cornell where I already wanted to go, in the major I wanted, operations research.

Over 130 people signed up for the One Year On Campus program in 1970. That was considerably more than Bell Labs had planned on; there was a mild recession and so more people accepted than they had planned. They didn’t retract any job offers, but the next year’s One Year On Campus class was much smaller, so I was lucky.

The last stage in applying was taking a physical at the local phone operating company. Besides the usual checks, you had to look into a device that had two lighted eyepieces. I looked in and recognized that I was seeing a cage in my left eye and a lion in my right eye. But I also figured out this was a binocular vision test and I was supposed to combine the two images and see the lion in the cage, so that’s what I said I saw. It’s unclear if Bell Labs cared about this, or this was the standard phone company test for someone who might be driving a phone truck and needed to judge distances. Next time I went to an eye doctor, I asked about this; after some tests, he said I had functional but non-standard depth perception.

What did you do for Bell Labs?

I worked in the Private Branch Exchange area. Large and medium size companies would have small telephone exchanges that sat in their buildings. It would be cheaper for them because most of the calls would be within the building rather than to the outside world, and thus avoid sending the call to a regular exchange a number of miles away and then back to the building. You could also have special services, like direct lines to other company locations that you could rent and were cheaper than long distance charges. The companies supplied their own phone operators and the operating companies were responsible for training, and the equipment and its maintenance and upgrades.

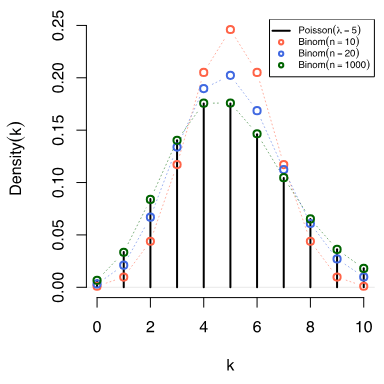

Most calls went through automatically e.g. if you knew the number. But some would need an operator. Naturally, the companies didn’t want to hire more operators than they needed to. The operating company would do load measurements and, if the number of calls that needed an operator followed a Poisson distribution (so the inter-arrival times were exponential).

The length of time an operator took to service the call followed an exponential distribution. In theory, one could use queuing theory to get an analytical answer to how many operators you needed to provide to get reasonable service. However, there was some feeling that real phone traffic had rare but lengthy tasks (the company’s president wanted the operator to call around a number of shops to find his wife so he could make plans for dinner (this is 1970)) that would be added on top of the regular Poisson/exponential traffic and these special calls might significantly degrade overall operator service.

I turned this into my Master’s thesis. Using a simulation package called GPSS (General Purpose Simulation System, which I was pleasantly surprised to find still exists) I ran simulations for a number of phone lines and added different numbers of rare phone calls that called for considerable amounts of operator time. What we found was that occasional high-demand tasks did not disrupt the system and did not need to be planned for.

Some projects I worked on:

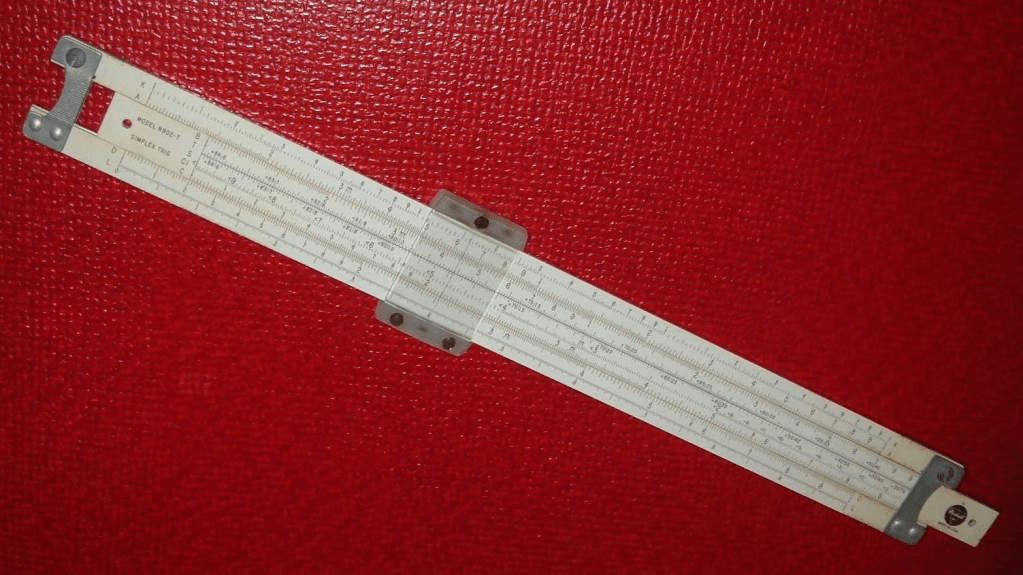

- A slide rule for salesmen to estimate prices on site, instead of making clients wait until the salesman could talk to engineering.

- Inventory control for parts for PBX.

- I worked with a Ph. D. mathematician on a complicated call processing problem. I ran a computer simulation and he expanded the standard queuing theory models to cover some of the complexities of reality. We compared results and they were reasonably similar.

Say more about inventory control?

The newest models of PBX’s had circuit packs (an early version of circuit boards), so that if a unit failed, the technician could run diagnostics and just replace the defective circuit pack. The problem was technicians didn’t want to get caught without a needed circuit pack, so each created their own off-the-books safety stocks of circuit packs. The operating company hated this because the circuit packs were expensive, driving up inventory costs, and further, because circuit packs were being constantly updated, many off-the-book circuit packs were thrown out without ever having been used. One operating company proceeded with inspections, which one technician countered by moving his personal stock to his home garage.

This was a classical inventory control problem, a subcategory of queuing theory. I collected data on usage of circuit packs and time to restock, and came up with stocking levels and reorder points. Happily, the usual assumptions worked out well. After a while, the technicians were convinced they were unlikely to get caught short, the company was happy that they had to buy fewer circuit packs and they were accessible to all the technicians. Everyone was happier.

And the slide rule?

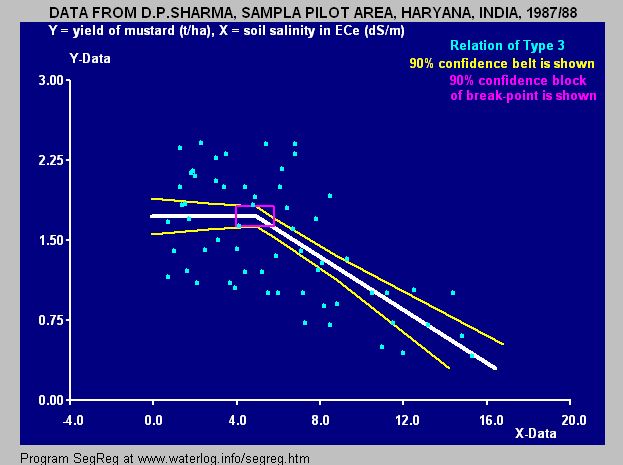

While I was in graduate school, I became interested in piecewise linear regression (aka segmented regression), where at one or more points the regression line changes slope, jumps (changing its intercept) or both.

I considered working on PLR for my Ph.D. dissertation. On my summer job back, I saw a great fit with a project. Salespeople would go out to prospective PBX customers but be unable to give them a quick and dirty cost estimate for a given number of phone lines, traffic load, etc. It was complicated, because there were discontinuities: for example, you could cover n phones with one control unit, so costs would go up linearly with each additional phone. But if you had n +1, you had to have two control units and there would be a noticeable jump in costs. There were a number of wrinkles like this. So the salesperson would have to go back to the office, have someone make detailed calculations and go back out to the customer, which would probably lead to more iterations once they saw the cost.

But this could be handled by piecewise regression. The difficult problem in piecewise regression is figuring out where the regression line changes, but I knew where they were: for the above example, the jump point was at n+1. I did a number of piecewise regressions that captured the important costs and put it on a ….

I bet you thought I was going to say a programmable calculator. Nope, this was 1975, and the first HP had only come out the year before. I had never seen one and wouldn’t own one for two more years. I’m not sure I could have gotten the formulae in the hundred line limit anyway. The idea of buying one for each salesperson and teaching them how to use them never came up. I designed a cardboard slide rule for them.

I found piecewise regression useful in my work. But that summer I recognized that research in the area had sputtered out after a couple of years, so I picked another topic for my dissertation.

Elizabeth: What did you do after your masters degree?

Craig: I worked at Bell Labs for a year, and then started my PhD in statistics at UWMadison. There were no statistics classes worth taking over the summer, so I spent all four summers working at Bell Labs.

How was Bell Labs organized, at a high level?

I interviewed for a job at Murray Hill, where the research oriented Bell Labs work was done. The job involved anti-ballistic missile defense and no secret details were gone into. I didn’t get that job. I worked in a more applied location at Holmdel.

I did go to one statistical conference at Murray Hill. The head of the statistical area there was John Tukey, a very prominent statistician. He simultaneously worked at Bell Labs and was head of the Princeton Statistics Department. You don’t see much of that any more.

There was a separate building in the area that did research in radio telescopes. This was an outgrowth of research that investigated some odd radio interference with communication, that turned out to be astronomical. I was never in that building.

However, Bell Labs didn’t skimp on the facilities at Holmdel. It had an excellent library with everything I needed in the way of statistics and applied math. The computer facilities were also first-rate, comparable to that at the University of Wisconsin where I got my PhD.

Holmdel worked with the operating phone companies who provided actual phone service in their own geographical areas. People at Holmdel would sometimes take exchange jobs at operating companies to better understand their problems. One of these came back from a stint in New York City and gave a talk where he showed a slide of people pushing a refrigerator out of an upper story window of a derelict building while a New York Tel crew was working underneath them.

A more common problem was that by the time I was there, technicians were not as bright as they had been. A bright person who could not afford to go to college or maybe even finish high school in 1940 and had become a technician in an operating phone company had kids who could go to college, become engineers and be about to start work at Bell Labs in 1970.

How was management structured?

My recollection was that a first line-manager had a mean of 8 or 9 people. This varied over time as projects waxed and waned. I have a feeling that new first-line managers had fewer people but I don’t ever recall hearing that officially.

There was a different attitude about people (or maybe it was a different time). My boss at Bell Labs had told them he was resigning to work at another company. An executive vice president came to visit him, said he had a bright future at Bell Labs and suggested he’d wait a while. He decided to and was soon promoted.

Feedback was mostly given by yearly performance appraisals, as it was at all the companies I worked for. Occasionally you’d get informal feedback, usually when some client was unhappy.

Bell Labs was big on degrees. To be a Member of Technical Staff you had to have electrical engineering classes and a Masters degree or on a path to get one. They were willing to pay for this.

What were the hours like?

For me it was a regular 9 to 5 job. I assume managers worked longer and more irregular hours but no one ever asked me to work late (I would have done if they’d asked). The only time I can remember not showing up at 9 was when I got in really late from a business trip the night before.

There was a story I heard while I was at Bell Labs which I have no idea is true. Walter Shewhart worked at Bell Labs. In 1956, he was 65, and under the law at the time, had to retire. The story goes that they let him keep an office, in case he wanted to stop by. Instead, he kept showing up at 9 and working until 5 every weekday. Eventually, they took the office away from him.

Who decided what you worked on? What was the process for that?

To be honest, I didn’t think much about that. I got my jobs from my first line manager. I kept the same one for my entire time at Bell Labs; I don’t think that was common. You may have noticed that I did a lot of work in the queuing and inventory area; my Master’s thesis was in that area and I’m guessing that my boss saw I was good at it and steered those kind of jobs to me. With my last task, getting a rough pricing approximation for PBX’s, I was handed the job, saw that piecewise regression was a great solution, talked to my boss about it and he let me do it that way. I don’t know how jobs got steered to him.

What was the distributions of backgrounds at Bell Labs?

I went with to Cornell for One-Year-On-Campus. Of the 5 people in my cohort: I was from Brown, one from Cornell, one from University of Connecticut and one from Indiana. So I’d say they were from at least good schools, so that the Labs would be sure they would be able to compete at Cornell.

Not everybody at the Labs came from elite schools. As the most junior member of the unit, who knew less about phones then anybody else, I didn’t enquire about their resumes. I was berated by one of members of my group for using meters for a wavelength in a meeting instead of “American units”. He had a second part-time job as a stock-car racer, but while I was there he decided to quit after his car was broken in half in a crash. Another man in my group had a part-time job as a photographer. When I came back from Cornell for my Christmas check-in at Bell Labs, he was dead in a train “accident”. Local consensus was that he had been working on a divorce case and got pushed in front of a train

My impression was that Bell Labs didn’t poach much from other technical companies. They wanted to hire people out of school and model them their own way.

Since the One-Year-On-Campus people were sharp and had Master’s, a lot of them got poached by other companies. Of the five people I kept track of, all five had left the Labs within five or six years.

As to age distribution, there were a considerable number of young people, from which there was considerable shrinkage year to year. After five to 10 years, people had settled in and there was less attrition. They were good jobs. Although not as numerous (I think because the Labs had expanded), there were a number of people who had been there for decades.

How independent was your work?

I did work with that Ph. D. mathematician on a queuing problem.

I can’t believe that they let me work on my own project in the two months between when I arrived at Holmdel before I left for Cornell. But I don’t remember what it was.

In retrospect, I am surprised that the Labs let me interview possible hires by 1972 when I’d only been around for a year (not counting the year at school). Admittedly, I was supposed to assess their technical competence. I think I did a good job; I recommended not hiring someone who they hired anyway. I later worked with her and my judgement was correct. She was gone within a year.

Tell me more about One Year on Campus

Bell Labs would pay tuition and expenses for a master’s degree along with 60% of your salary, as long as you graduated in the first year. There also was an option to stay on full salary and go to grad school part time, but I didn’t do that. You could theoretically do this for a PhD but it was much harder to get into; I only knew one person in my division who did so.

One qualification was that you had to have a year of electrical engineering (or spend a year at the Labs before going). Fortunately, although my degree was in Applied Math, I had taken some electrical engineering as an elective. Partially out of interest, and partially because my grandfather had worked his way up to being an electrical engineer [note from Elizabeth: this was the grandfather on the television patent].

An important caveat was that you need to get your degree completed in a year or you would be fired. I never heard of this actually happening, but I was motivated.

Bell Labs would also pay for you to take classes part-time and give you a half-day off; I went to the stat department at Columbia and took my first design of experiments class there and fell in love.

What was so loveable about experimental design?

My love affair with design of experiments started in my first class on the subject. The professor told a story of attending at a conference luncheon at Berkley and was seated between two Nobel laureates in physics. One of them politely asked him what he did and the professor gave him this weighting design example.

You have a balance beam scale, where you put what you want to weight on one side and put weights on the other side until it balances. You’re in charge of adding two chemicals C1 and C2 to a mixture. They come in packages with nominal weights, but the supplier is sloppy and the precise ratio of them is important to the quality of the mixture. However, this is a production line and you only time to make two measurements per mixture. What two measurements do you do?

The obvious answer is you weigh C1 and then you weigh C2.

But this is wrong. A better solution is to put C1 and C2 in the same pan and get their combined weight WC. Then you put C1 in one pan and C2 in the other, and you get the difference between them, WD. Then if you add WC + WD, the weight of C2 cancels out and you get an estimate of 2*C1. If you subtract WD from WC, the weight of C1 cancels out and you get an estimate of 2*C2. Notice that you’ve used both weighings to determine both weights. If you run through the math, you get the same precision as if you weighed both chemicals twice separately, which is twice the work.

The physicist got excited. The other Nobel laureate asked what they were talking about, and when he was told, said: “Why would anyone want to measure something more precisely?”. That is the common reaction to the design of experiments.

But even more important than efficiency, designed experiments can inform about causality, which is very difficult to determine from collected observed data. Suppose there is impurity that varies in a feedstock that is fed into a chemical reactor that lowers the quality of the output but we don’t know this. The impurities also cause bubbles, which annoy the operator, so he/she increases the pressure to make them go away. If we look at a plot of quality vs. pressure, it will look like quality decreases as pressure increases (when actually it has nothing to do with it; correlation does not imply causality). But if we run a designed experiment, where we tell the operator which runs are supposed to be run at high pressure and which are to be run at low pressure, we have a good shot of figuring out that pressure has nothing to with quality (the greater the number of experiments, the better the odds). If we then talk with the operator and they explain why they increase pressure in production, we have a lead on what the real problem might be.

What if you don’t care about efficiency or causality? The following example is borrowed from Box, Hunter and Hunter “Statistics for Experimenters”, first edition, pp. 424ff. A large chemical company in Great Britain makes fertilizer. Because the cost of fertilizer is low, transportation costs are a noticeable part of it, so when demand goes up, instead of adding onto a current plant, they build a standard plant at a blank spot on the map. Unfortunately, this new plant’s filtration times nearly doubles, meaning this multi-million pound plant (currency, not weight) is operating at half capacity. Management goes nuts. There is a very contentious meeting that comes up with 7 possible causes. Box comes up with a first round plan to run 8 experiments. This is the absolute minimum, since we need to estimate the mean and the seven effects. This is important, because we’re not doing experiments in a flask, but in a factory. Changing one factor involves putting a recycle device in and out of line, etc., so it won’t be quick.

What do you do? The usual reaction is to do a one-at-a-time experiment, where we have a base level (the settings of the last plant previously built) and then change one factor at a time. This is generally a bad idea and, as we shall see, this is a particularly bad idea in this case. First, as a multiple version of the weighing design, we only use two points out of the eight to determine the importance of that factor. And suppose we botch the base level?

Instead, Box did a fractional factorial design, with eight design points such that we code a factor levels as 1 if it’s at the factor level of the working correctly plant and -1 at the new plant’s settings.

Then if we add the four settings of, say factor 1, that are 1 and subtract the four that are -1, we estimate 8 times the distance between the new pant and the neutral 0 settings and and all other factors are at their neutral setting. Similarly for all the factors. Box used the fractional factorial design that included all old plant settings. Its filter time was close to the old plant’s, which reassures us we have captured the important factors. If we do the same for all factors, the magnitudes of factors 1, 3, and 5 are considerably larger than the other four. However, chemistry is interaction and each of the large magnitude factors is confound with the two-factor of the other two large magnitude factors. Fortunately, we can run an additional eight runs to estimate triplets of two factor interactions, because we didn’t blow our whole budget doing one-at-at-time experiments. It turns on that the triplet that includes factor 1*factor 5 interaction has a large magnitude interaction, which could reasonably explain why the original factor 3 estimation magnitude appeared to be large. However, management wanted to be sure and ran a 17th experiment with factor 1 (water) and factor 5 (rate of addition of caustic soda) at the old plant settings and the other 5 were left at the new settings. The filtering time returned to the desirable level. Notice if we had done a one-at-time experiment we would never have been able to detect the important water*(rate of addition of caustic soda). There is a feeling that a lot of tail-chasing in industrial improvement is due to interactions not being recognized.

Another element of experimental design is blocking, where we suspect there are factors that we care about, like four different types of fertilizer and others don’t care about (say hill top land, mid-hill land and bottom land) but may effect the yield. The solution is to block so that each of the four fertilizers gets an equal share of the three land types. This eliminates the noise due to land type

Finally, within the limits of blocking, we wish to randomly assign treatments to factor settings. This provides protection against factors that we don’t realize make a difference. There was a large stage 2 cancer vaccine study which showed that the treatment group lived 13 months longer than the control group. The only problem was that who got the treatment was not decided at random but by doctors. It went on to a much more expensive stage 3 trial, which found no statistically significant difference between the vaccine and the control groups. What happened? It is surmised that since doctors can make a good guess at your prognosis and desperately want to have another tool to fight cancer, that they unconsciously steered the less sick patients to the vaccine group.

Thanks to my Patreon Patrons for supporting this post, and R. Craig Van Nostrand for his insider knowledge