There’s one more big food hormone everyone talks about: insulin. The visiting doctor on local news explanation of insulin is that it is produced by your pancreas in response to sugar in order to signal all your other cells that sugar is available in the blood stream and they should eat it. The truth is, of course, more complicated.

First, your pancreas is producing insulin all the time*. It then stores in the insulin until triggered. This makes sense: demand for insulin is very spikey, and producing it all on demand would require an enormous number of cells that would be idle much of the time. The sugar thing is a simplification as well. Chemicals other than sugar stimulate insulin release, and not all types of sugar stimulate release. Insulin is released by glucose in the blood (and by mannose, a sugar that looks very similar to insulin), but not fructose (which has fewer carbon atoms), but also amino acids**. How much each amino acid stimulates production appears to be an open question. This paper suggests all essential amino acids stimulate production greatly , this one says leucine, phenylalanine, and arginine (not considered essential in health adults) are the strongest, this one says arginine, lysine, alanine, proline, leucine and glutamine. We’ll cover why this may matter in a minute.

Just like ghrelin and leptin act as semi-antagonists, insulin has its own nemesis: glucagon. Where insulin stimulates your cells to take in sugar (and protein), glucagon stimulates your liver to release stored sugar. This is necessary for keeping energy levels up when there is no immediate dietary source of sugar. Glucagon also stimulates your body to break down protein (dietary or, in a pinch, your own muscles) for energy. Remember how we said fasting could lead to muscle growth by stimulating growth hormone production? Well it also leads to breaking down your muscles for energy, via glucagon.

Insulin and glucagon are in a very delicate balance. When you eat a high-protein meal and have adequate energy levels, your body would like to use that protein to build enzymes and muscles and things. To do this it must release insulin, which triggers your cells to take in amino acids from the blood. But insulin also triggers them to take in sugar. If the meal did not contain enough sugar***, this will send your blood sugar level dangerously low. So your body preemptively releases glucagon, which triggers the release of stored sugar, thus maintaining blood sugar levels at optimal. But! what if you’re on a chronically protein-rich, sugar-deficient diet? This pattern could cause you to starve to death. So glucagon also causes your liver to take in amino acids and use them for energy (which it can then distribute throughout the body).

What I’m wondering is if glucagon and insulin respond to differently to different amino acids. Specifically, if essential amino acids cause a larger [insulin – glucagon] than non-essential ones. That would allow your cells to preferentially take in the most necessary amino acids, while leaving the less necessary ones for glucogenesis, which would certainly be handy. Alas, I cannot find any studies on individual amino acids and glucagon. This may be moot, since my impression is that the modern amino acid mix is pretty much closer to the paleolithic amino acid than sugar or fat are, so our system probably handles it better.

Your pancreas is a real go getter that wants to be prepared for extra sugar, because excess blood sugar is actually pretty damaging. To do this it looks releases not just enough insulin to cover current blood sugar levels, but what it anticipates those levels will be in the future. The problem is that it’s prediction algorithm is woefully out of date. It may not even have caught up to farming (whoohoo, wheat and rice!), much less modern hyperprocessed snack foods. If you eat a small piece of candy, your body doesn’t release enough insulin to handle the candy. It looks at the sugar level and assumes you just ate something enormous and releases an appropriate level of insulin.

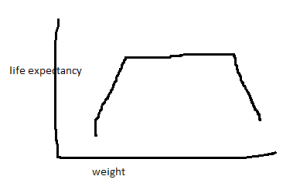

When the rest of the sugar and protein fail to appear, your blood sugar level drops precipitously. I don’t even know what it does to your blood or cellular protein levels, but it can’t be good. Over time, your muscle cells may get tired of your pancreas’s false promises and stop listening to its pleas. But the fat cells never stop listening. This means that when you do eat protein or sugar, your fat cells take in a disproportionate amount of both. If this progresses too far you get type II diabetes.**** Meanwhile, your glucagon production is completely unchanged, so your liver is happily taking in protein for energy synthesis (which frees up sugar to make fat). This means it is perfectly possible to get fat as the rest of your body starves.

Oh, and one more thing affects insulin and glucagon production: stimulation of the vagus nerve. Saying “vagus nerve” is only slightly more helpful than just saying “the body”, because the vagus nerve goes everywhere. This article suggests that it’s carrying a signal from the liver to reduce insulin production. This study stimulated the vagus nerve below the heart and found it raised both glucagon and insuline levels. This study found removing the (hepatic?) vagus nerve in rats reversed type 2 diabetes. I’m going to put this down as “the digestive system is actually much smarter and more communicative than we realize.” I’m also curious about the fact that the vagus nerve also extends into the face, where it can detect chewing, but can’t find any studies on it.

Insulin probably doesn’t make you feel or full in the classic sense, but it can drop your blood sugar, which will make you slow and sleepy until you eat more food (“hey, a candy bar would wake me up…”), but it can stimulate leptin production and release which will make you feel full (and is another strike against leptin as The Ultimate Fat Barometer). Glucagon probably is an appetite suppressant, which I find counterintuitive, and probably means it plays a bigger role in protein digestion than weathering long term calorie deficits.

What I find most amazing is that I have a biology degree, and didn’t realize insulin had anything to do with protein until just now. We talk about insulin/sugar/diabetes/fat so much, we miss the protein/strength/cellular activity level. I do not like what this implies at all

*And the brain. Like leptin, insulin appears to make your brain feel safe to expend energy. But at least not in the lungs this time.

**Reminder: The human body builds proteins out of 21 different amino acids. Some of these it can produce itself, some must be taken in from the environment (essential amino acids). Amino acids can also be used to generate energy, although this produces more ugly byproducts than sugar or fat, to the point it’s actively unsafe at higher levels.

***Admittedly less of a problem now than it was in the evolutionary relevant time period.

****Type 1 is a simple problem of insufficient insulin production. Injecting insulin isn’t a perfect cure because you can’t perfectly replicate the sensitivity of the pancreas, but it is pretty close.